Loving Vincent – Like Watching Paint Dry

Runtime: 95mins | Director: Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman | Rating: 2 Stars

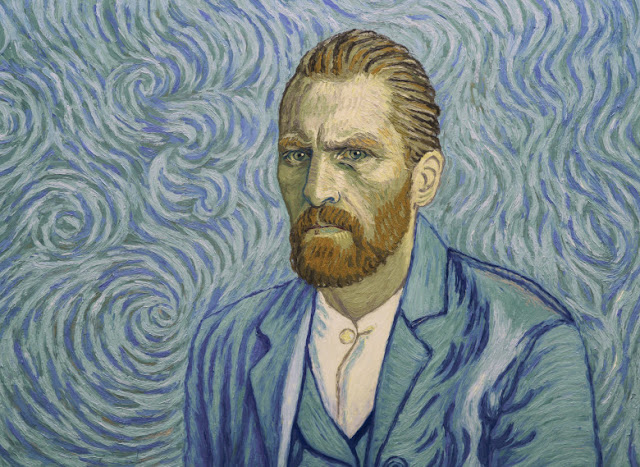

Loving Vincent has made history by being the first feature film to be entirely oil painted. Unfortunately, however, it was also like watching paint dry both metaphorically and literally.

Loving Vincent has made history by being the first feature film to be entirely oil painted. Unfortunately, however, it was also like watching paint dry both metaphorically and literally.

For those who know little about the film (which wouldn’t surprise me due to its very limited advertisement), it explores the incredibly tragic life of Vincent Van Gogh – a man plagued by insecurity and mental instability. When alive, people thought he was a mad-man and no-one cared for his art. It was only once he died that his paintings became so highly coveted and recognised as some of the greatest artistic works ever created.

Infamously, after an argument with a close friend, Van Gogh took a razor blade and cut his ear off which he then presented to a prostitute in a brothel. Several months after attempting to improve his mental health under the care of Paul Gachet, he then shot himself in the chest after sinking back into his depression. As a result, Van Gogh is often looked at as one of the defining examples of a stereotypical troubled artistic genius, and whilst morbid, it’s unsurprising his troubled life has been dramatized.

Loving Vincent begins after the above events when Postman Roulin (Chris O’Dowd), a friend of Van Gogh’s, asks his son, Armand (Douglas Booth), to deliver an unopened letter of Van Gogh’s to his brother after it failed to do so on previous attempts. Whilst on his journey to deliver the letter, Armand finds himself becoming more invested in finding out the ‘truth’ of what happened to Vincent as many things don’t seem to make sense. Whilst attempting to discover the truth of his death, this leads Armand to meet many people from Van Gogh’s past who all seem to have different recollections of him and suspicions about the circumstances of his demise.

Firstly, it cannot be denied that this film is beautiful to watch. Aesthetically, it is astounding. The level of detail in the paintings is truly incredible and it’s unsurprising that the film took over six years to make with over 65,000 painted frames created for it by over 125 “specially trained painters”.

Ultimately though, a film can’t expect to rely solely on its visuals to be deemed as ‘good’ (take note Blade Runner), and this is Loving Vincent’s Achilles heel – it does solely rely on its visuals and I can’t help but feel that the film encapsulates the well-known phrase ‘art for art’s sake’. It’s all well and good to try and create a record-breaking film, but if it lacks an engaging narrative (which this did) then it will be quickly forgotten with its record left to gather dust.

Due to the investigatory nature of Armand’s journey, the film can easily be classed as a detective film. When you watch a detective film, however, you expect some form of a narrative resolution at the end where everything ties together and you get your “if it weren’t for you meddling kids!” moment. Disappointingly, you don’t get anything of the sort with Loving Vincent which makes it infuriating. Furthermore, it lacks energy - at no point was I fully engaged or invested in any of the characters which when you’re watching a film about a painter from the 1800’s (not the most interesting of topics unless you’re an art-buff, I’d argue) is vital to keeping your audience engaged, which Loving Vincent didn’t. This was made amusingly apparent when half-way through the film, the cinema was drowned with the snores of a woman who had fallen asleep.

Ultimately, whilst I appreciate Loving Vincent for what it attempted and for the incredible amount of time and effort that was put into it, I can’t justifiably say it is a good film. For a film to be good, it needs to excel in all key components, not just its visuals. Loving Vincent will appeal to a very niche market of art aficionados who’ll derive joy from its many artistic Easter eggs, but aside from that, I can’t imagine anyone else enjoying it, which is a shame. Perhaps this would have been better as a special screening at the Tate or other international art galleries rather than as a general release film.

Comments

Post a Comment